Several figures have been used to describe the gender gap in academia and research, from “leaky pipeline” to “glass ceiling”. But what are the experiences of girls and women in the scientific community? We have tried to gather together our perspectives as young women starting our careers in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) field, reflecting on the past formative years and wondering about our future prospects.

It is undeniable that our childhood and school years have a great influence on our interests and on the person that we become as adults. There is still a considerable disparity between the education provided to male and female children around the world. Patriarchal and obsolete gender roles are still engraved in the way society teaches young boys and girls: from the toys that we are given to the life lessons we are told. This lack of equal education is leaving women in a skills crisis when it comes to STEM and high responsibility jobs [1]. Another issue is the under-representation of successful female role models in science. Let’s be honest, at most people would be able to name Madame Marie Sklodowska Curie if asked on the street to name a famous female scientist. Young girls do not have a mirror to seem themselves in when it comes to dreaming of becoming a researcher. As a consequence, women are unmotivated to try a career in STEM, feeling ashamed to speak up about their passion and discriminated against in case they do.

One of us had a strong model growing up: her grandmother who, in the mid-1900s, chose a career in physics, facing a world that was encouraging women even less to pick their own path. We recognize now the importance of representation: it makes everything you imagine obtainable and possible.

With our short experience as PhD students, we would like to send out a few words of encouragement to girls who are interested in science and research. But first, let’s have an idea of the situation we are delving into.

More than 500 000 people were studying Science (Biology, Chemistry, Physics and Mathematics) in the European Union (EU) in 2018 at a Bachelor or Master level (or equivalent). Overall, women were under-represented, accounting for roughly 46% of all Science students in the EU. However, this number is not representative as there is a strong disparity amongst the subjects of study. Indeed, less than 30% are female students in Physics against more than 60% in the field of Biology.

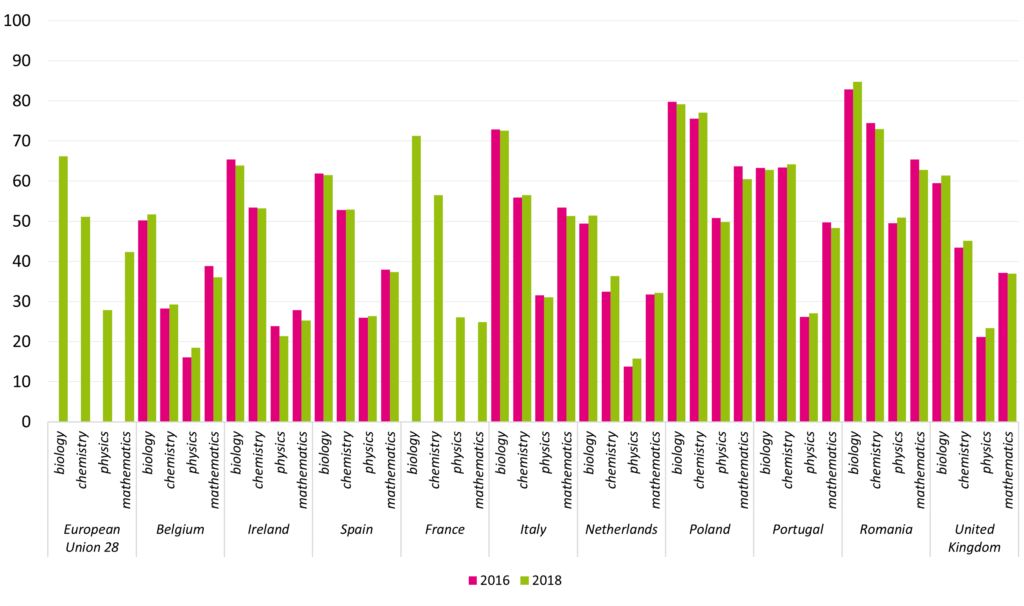

In Figure 1, the share of female students in different fields of Science in 2016 and 2018 is represented for the countries that are part of the Pioneer consortium. Among the EU Member States, Romania and Poland stand out with more than 50% of female students in the four fields considered. In contrast, the share of female Physics students is less than one fifth in Belgium (18.5%) and the Netherlands (15.7%). Excluding Romania and Poland, the highest shares of female students in Mathematics were recorded in Italy (>50%) and Portugal (>40%).

Concerning the evolution between 2016 and 2018, the general trend would suggest an increase of the number of female students in Science. The field mostly concerned by this increase is the field of Physics, with a growth in all the countries considered except Ireland, Italy, and Poland.

Figure 1: Share of female students in different fields of Science in 2016 and 2018 for the countries that are part of the Pioneer consortium. Data source: ec.europa.eu/Eurostat. [2]

When discussing the gender gap the term STEM is mostly used and refers to subjects such as Astronomy, Biochemistry, Biology, Chemical engineering, Chemistry, Computer science Electrical engineering, Mathematics, Physics, Statistics… the issue of female underrepresentation and lack of female role models in STEM subjects has been discussed extensively and is often blamed for steering women away from studying these subjects. Indeed, it reinforces the perception that women will feel isolated and excluded in these typically male-dominated environments. In order to encourage more female students to choose a STEM degree, universities, employers and governments have also introduced policies aimed at increasing the proportion of women but the effects of these policy instruments are difficult to assess and there is still a long way to go before equality is reached. Universities can also fight the gender gap by creating new interdisciplinary scientific fields as it was shown that women would be more drawn to this type of research. Finally, efforts should be made to increase the exposure of positive female role models both in schools and in universities.

We have discussed the disproportion between men and women in STEM at BSc and MSc levels. These numbers remain below 40% at doctoral level, where we find 37% and 39% of female PhD students and graduates, respectively [3]. If we compare these data to the corresponding shares in all fields, we see that European early stage researchers are almost reaching parity on a gender basis, while women in science and technology suffer from a drop of 11 and 9 percentage points respectively, in the same positions.

There are however differences between all EU Countries, with some doing better than others, as well as more marked disparities depending on the discipline within the broad STEM category. For instance, physics and engineering have the worst female participation, while the number of women in natural sciences, biology and chemistry is increasing at a faster rate, mirroring the same trends we saw for undergraduate and postgraduate students.

How are universities and institutions tackling this problem? Gender equality has been included among the 17 Sustainable Development Goals in the 2030 EU Agenda. We have examined the websites of the 15 Universities taking part in our Consortium, to have a general picture of the situation in Europe. The majority of them has a dedicated webpage on gender equality and diversity, where its policies and resolutions are listed. Only two Universities (U. of Trento and U. of Zaragoza)[4][5] have an actual Monitoring Center that provides public progress stats on a yearly basis, confirming the need to fill huge data gaps. We strongly encourage all universities to take a leaf from them, to be more effective in their actions for the achievement of equality. A special mention goes to the University of Liverpool for its LivWiSE project (Liverpool Women in Science and Engineering society) [6], for their outstanding work on promotion, networking and event organization. We really recommend you to visit their webpage and youtube channel.

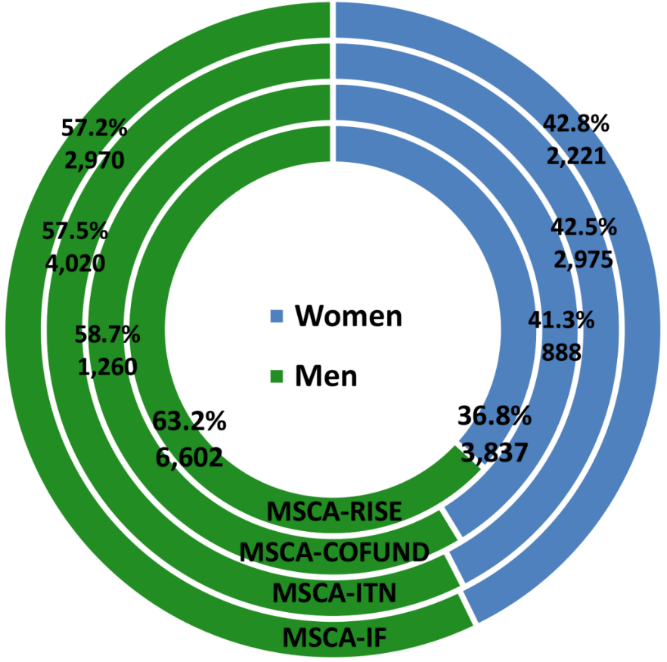

Across all the EU Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions (MSCAs) funded between 2014 and 2018, the average presence of women accounted for 40,9%. Specifically, the Doctoral programmes MSCA-ITN (Innovative Training Networks) registered 42,5% presence of female researchers. In the frame of Pioneer, only 1 out of 3 ESR is female, which is way below the general share.

To conclude, a doctorate is a period of intensive training and the beginning of a research career in an elective field. Women must not be cut out from the technological and scientific advancement and from shaping tomorrow’s world. Finally, “there is overwhelming evidence that diverse teams are more creative and productive”, as Frank Baaijens, Rector of Eindhoven TU, declared, speaking about the University’s resolutions to increase women’s and minorities’ representation in academia. [7]

With this overview of the current situation of gender gap in university, we are looking ahead at the future scenarios and prospects for our professional careers. Nowadays, it can be said that finding a proper job and becoming a successful professional is one of the biggest challenges in one’s life. In today’s society, based on living cost, usually in each family both parents are employed. With progress in education and industry, unlike the previous generations, the last two generations are well educated and the competition for employment has increased. But the question is: are all these opportunities equal for women and men? Statistics show that in EU (Schengen Area) the employment rate of men is 11.8 percentage points higher than for women, despite the fact that the population of women in working age is 51% and for men is 49% [9]. Moreover, women are generally paid less with hourly earnings on average 14.8 % below those of men [10]. It seems that even in developed countries, there is still gender inequality in the workplace.

Compared to men, especially in technical positions, women are still not considered as experts. For example, imagine there is a job opportunity as an engineer in a company, there are two candidates: one woman and one man with exactly same credentials. Most likely, the man is going to be chosen based on prejudices that picture male professionals as more suitable and more educated in STEM field. Of course, with such point of view coming from society, women are less confident and usually underestimate themselves. Just imagine in such environment how women are under pressure to prove their perfection. Even if they are selected for a job, they always have these thoughts in mind that they should prove themselves to their peers. A study showed that, in the same workplace if you ask a man and a woman what they are mostly thinking about during their work is that the man thinks about improve his work because he is sure of his perfection in the work and the woman thinks about to compete with other colleagues just because of lack of confidence.

Just being a woman is a big challenge to face inequalities, so you can imagine how much harder is to be a successful woman. It’s still long way to show the societies that being a successful woman is not just being a good mother or wife. Women’s share in science and industry is much bigger than what we think. We have to rely on our set of skills, our solid preparation and our passion to show the world that these gender biases are outdated and a new generation of girls in STEM is ready to tackle the challenges of tomorrow.

Stay tuned for the second part of the blogpost in honor of the International Day of Women and Girls in, we will be reflecting on these important topics with some of the PIONEER supervisors.

This text was written by Beatrice Musig, Chloé Fromentin, Marzia Faedda, Golshid Hasrack and Carolina Garcia.

Sources:

[1] “https://www.unicef.org/media/84046/file/Reimagining-girls-education-through-stem-2020.pdf,” [Online].

[2] Dataset ‘Pupils and students enrolled by education level, sex and field of education’ “https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/educ_uoe_enra03” (Accessed on 31/01/2021)

| [3] | “https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/she-figures-2018_en,” [Online]. |

| [4] | “https://www.unitn.it/en/ateneo/53111/equality-diversity,” [Online]. |

| [5] | “https://observatorioigualdad.unizar.es/,” [Online]. |

| [6] | “https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/liverpool-women-in-science-and-engineering/,” [Online]. |

| [7] | “https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jun/19/female-academics-job-applications-men-engineers,” [Online]. |

| [8] | “https://euraxess.ec.europa.eu/worldwide/japan/gender-equality-policies-and-gender-distribution-msca-and-erc,” [Online]. |

[9] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Gender_statistics [Online].

[10] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Gender_pay_gap_statistics [Online].

Extra references: Pioneer Universities Gender Equality webpages

Sorbonne Université

https://sciences.sorbonne-universite.fr/faculte/presentation/egalite

TU/e Eindhoven

https://www.tue.nl/en/our-university/about-the-university/diversity-and-inclusion/

DCU

Tecnico Lisboa

https://tecnico.ulisboa.pt/en/campus-life/living-at-tecnico/diversity-and-gender-balance/

AGH Krakow – no gender equality webpage

University of Bucharest – National Gender studies ban (https://www.euronews.com/2020/06/17/romania-gender-studies-ban-students-slam-new-law-as-going-back-to-the-middle-ages)

University of Trento

https://www.unitn.it/en/ateneo/53111/equality-diversity

University of Antwerp – Master in Gender studies but no committees for gender equality

University of Liverpool

https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/hr/diversityandequality/

https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/liverpool-women-in-science-and-engineering/

video https://youtu.be/MwOPN71CAlc

University of Caen – no webpage dedicated

University of Zaragoza

University of Paris-Saclay

https://ens-paris-saclay.fr/en/actualite/gender-equality-workplace-not-just-question-expertise